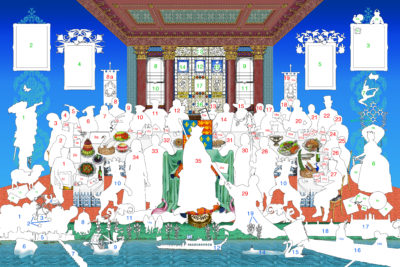

Singh Twins Artwork

KEY – FOR DETAILS IN THE ARTWORK NUMBERED IN RED:

1 and 1a – A member dressed as a Roman Emperor, and a postcard of Phoenician textile merchants. These represent the role of the ancient Mediterranean world in the production, acquisition and trade in dye materials and dyed textiles. The figure’s purple cloak in particular, represents Tyrian purple – an expensive colour acquired from shellfish which was associated with royalty in the ancient and medieval world and was one of the Phoenician’s most famous exports.

1b and 1c – murex snails representing shellfish (from which Tyrian purple was made) and an engraving representing lichen – two examples of natural world sources for dye (one from the sea, the other from land).

1d – A framed picture based on an early 19th century engraving of Dyers’ Hall as it existed between 1770-1838. Located on College Street it represents the site of the current Hall which replaced it in 1841. The fact that the picture is held by the Roman figure symbolises the discovery of Roman archaeological remains under the Hall.

2 and 2a – A member dressed as English poet and author Chaucer. This represents the recording of dyers in early literature – in particular, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales* which is represented by 2a (showing the reproduction of a miniature painting from a medieval illuminated manuscript** inspired by Chaucer’s work which depicts its author with Canterbury Tale pilgrim guildsmen) and 2b (showing an engraving and extract verses from a later published version of Canterbury Tales***, in which the dyers are mentioned).

* A collection of 24 stories written by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 – 1400

** ‘The Siege of Thebes’, by John Lydgate, Royal MS 18 D II, f, 148r – British Library collections. Miniature painting attributed to Gerard Horenbout c1516-1523.

*** From ‘The Penny Magazine’s Chaucer’s Portrait Gallery’, Published by Charles Knight and Co.1841.

3 and 3a – A member dressed as the Anglo-Saxon king ‘Edward the Martyr’ drinking out of a two-handled silver loving cup (3a) from the Dyers’ collection, used for ceremonial occasions.

3b – A Minton China Works tile designed by John Moyr Smith depicting how, by some accounts, Edward the Martyr was murdered whilst drinking from a cup, as the need to use both hands to hold the vessel left him vulnerable to attack. This event is said to explain the origins of the established ceremonial tradition of drinking from a loving cup with a companion watching out by your side.

4 and 4a – A member wearing the Coventry City Football team home shirt, with the team scarf on the table in front of him.

5 – A member dressed as Robin Hood in Lincoln green.

Collectively 4 and 5 represent not only how with the emergence of centers for dyed fabric in Britain certain colours became associated with and named after particular regions, towns and cities, but also, how those historical colours have impacted on modern day culture. The two colours represented here are Coventry blue and Lincoln green. Coventry blue was a blue cloth woven and dyed with woad in Coventry. The permanence of the colour led to the phrase “as true as Coventry blue” or “true blue”. The Coventry City Football kit featuring a blue which led to the team being nicknamed the Sky Blues, is used to symbolise Coventry’s historical connection to blue.

Lincoln green is the colour of dyed woollen cloth formerly originating in medieval Lincoln. In popular culture it is probably most often identified with the outfits of Robin Hood and his Merry Men in Sherwood Forest, Nottingham. However, the scarlet under sleeves of the Robin Hood outfit in the artwork reveal a lesser known fact. Namely, that these once highly prized Lincolnshire cloths were dyed in both green and a shade of red (more expensive than the green) called Lincoln scarlet. Lincoln scarlet was known then as Lincoln graine or greyne: a word (relating to the graintree oak and by affiliation the Kermes or graine beetle which lived on it and from which red dye was obtained) which down the ages may have been corrupted to ‘green’ – thereby explaining the predominance of green over red, as the colour most associated with Lincoln in popular imagination.

5a – The Robin Hood figure is shown holding woad and weld (5a) which were two indigenous plants of England used to create green and red at that time. These plants are also shown in the foreground of the artwork growing along the river bank (19).

6 – A member dressed as King Henry VIII (after a portrait by Holbein), whose dissolution of the monasteries (where monks were the traditional practitioners of dyeing) effected the craft of dyeing. Henry was also responsible for ‘demoting’ the Dyers from the position (12th) they enjoyed as one of the ‘Great Twelve Livery Companies’ of London – allotting it instead to the Clothworkers who were formed from a merger of The Fuller’s Company and The Sherman’s Company in 1528. The Dyers have remained in 13th position ever since.

6a – An engraving depicting Henry VIII surrounded by the coats of arms of each of the 12 great Livery companies of London (notably excluding the Dyers). Titled, Ill May Day, the engraving (after a picture by John Leighton) was published in an 1860 edition of the Illustrated London News with an accompanying article relating to anti immigrant riots which took place in 1517 during the reign of Henry VIII. The article highlighted the prejudice towards ‘strangers’ workers in England at that time, many of whom were from the dyer and cloth worker communities.

7, 7a, 10 and 10a – Following on from the story of how the Dyers lost their ranking as one of the 12 ‘Great Twelve Livery Companies’, to the Clothworkers (see 6 above), these two figures represent the now amicable relationship between the Dyers and Clothworkers. This is symbolised by the figure on the left (representing the Dyers) who in a gesture of friendship offers a hatchet* (7a) to the figure on the right (representing the Clothworkers). Whilst the figure on the right is shown holding an invitation (10a) for a dinner hosted by the Dyers at Clothworker’s Hall – pointing to a spirit of collaboration.

* The hatchet in the artwork is a copy of the one used for an actual ‘passing of the hatchet’ ceremony acknowledging better relations between the Dyers and Clothworkers, which has been adopted in more recent years at an annual ‘Bury the Hatchet’ dinner when both Companies meet.

8 and 8a – A member dressed as Sir Robert Tyrwhitt the first major benefactor of the Dyers. Behind him is a banner (8a) bearing the Tyrwhitt coat of arms and an antique engraving* depicting the land he bestowed on the Dyers in 1545** which was the site of their first Hall and became known as Dyers Wharf. The costume is based on the suit of armour worn by a stone carved figure of Trywhitt on the memorial to himself and his wife at All Saints’ Church, Bigby, Lincolnshire. His close proximity to Henry VIII within the artwork denotes the fact that he was brought up at the royal court, became deputy chamberlain of Henry VIII and one of the first to receive a royal grant of monastic lands after the dissolution of the monasteries.

* The engraving which shows dyers washing their dyed cloth in the Thames, is after a painting by Samuel Scott – a copy of which hangs in Dyers’ Hall.

•• cited from Hubner-A Contribution to The History of Dyeing, p1045 (Journal of the Society of chemical Industry, Vol. XXXII.,No.22, p1043 -)

9 – A member dressed in the style of a Tudor lawyer after a portrait* of a Legal Notary by Quentin Massys (1466-1530). The portrait has been adapted by the artists who amongst other things have added several crowned portcullis emblems (representing Parliament) and coloured horizontal and vertical stripes to the lawyer’s robe. This imagery points to how the craft of dyeing was regulated by law – such as in 1552 when in response to competition from the New World, the dyers’ colours were fixed to 16 shades. These 16 shades correspond to the coloured stripes.

* In the National Gallery of Scotland collections, Edinburgh.

10 – see point 7 and 10 above.

10b and 10c – an antique woodcut engraving* depicting English dyers and an illuminated painting** depicting Flemish dyers at work. These two images depict processes of dyeing at different times and geographic locations which find a connection through the knowledge skills that dyers from Flanders (and Holland) imparted to their English counterparts after Edward III encouraged them to establish their trade in England during the 14th Century following their exile from Flanders. The illuminated manuscript painting also represents the admittance of Flemish Dyers into the English dyehouse at Southwark in 1556.

* From The Book of English Trades and Library of the Useful Arts, c1821.

* * The original illuminated painting appears on folio 269 of book III (titled, Le Livre de la propriété des choses) of a French translation of De Proprietatibus Rerum – created in 1482 by Bartholomaeus Anglicus and currently in the British Library Royal Collection. Ref: Royal MS 15 E II-III: 1482.

11 and 11a – A member dressed as Charles V (after a portrait* of Charles V by Jakob Seisenegger, 1532), Holy Roman Emperor Austria, King of Spain, Lord of Netherlands and Duke of Burgundy. He represents how global politics and power connect to the history of dyeing in that his domains included regions (such as Flanders and Burgundian Netherland) which were the traditional homelands of non-Catholic European communities of weavers and dyers whose migration to England due to religious persecution under Charles V (and at other times) would influence the story of dyeing in Britain. As head of the rising House of Habsburg (represented by 11a – the Habsburg coat of arms) during the 16th century, he also represents a family and class of nobility who were important patrons of textile arts such as tapestry making which depended on the craft of dyeing.

* The portrait, titled, Emperor Charles V with Hound (1532) is now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

12 and 12a – A member dressed as William Shakespeare (after the Cobbe portrait of 1610). This represents the reference to Dyers in Shakespeare’s sonnet 111 – the relevant extract from which is inscribed on the paper held by the figure in the Twins’ artwork. A miniature version of the Globe Theatre on the table in front of him, denotes the modern day Company of Dyers’ support of the Theatre’s recreation on the South Bank in 1997.

13 and 13a – A figure wearing a T-shirt printed with Channel 4’s ‘Grayson’s Art Club’ logo, and holding a poster (13a) depicting The Singh Twins with their artwork NHS v Covid:Fighting on Two Fronts. These details represent the history behind the commissioning of the Dyers’ 550 artwork as it was the Twins’ appearance as guest artists on this Channel 4 series (in which they talked about their NHS piece) that led to their being asked to create a commemorative artwork for the Dyers.

14, 14a, 14b and 14c – A member wearing the British colonial ‘red coat’ uniform which became an established part of English military attire after the expensive red (carmine) dye produced from Kermes beetles was replaced by a cheaper, more durable, brilliant, ‘perfect red’ dye initially known as Drebbel’s scarlet – named after its Dutch inventor Cornelius Drebbel (14a) who discovered it whilst making a thermometer around the year 1606/07* when some tin (represented by detail 14b in the artwork) and aqua regia accidentally fell into a bowl of water dyed with organic cochineal pigment processed from the female coccus insect (14c). The dye was also known as both ‘Bow red’ (after the street in London where Drebbel’s son-in-law Abraham Kuffler owned a dyehouse and produced the dye) and ‘color Kufflerianus.’

* Some accounts place the invention at a later date.

15 – A member dressed as Sir Cuthbert Aket* (alias Hacket) – The English merchant who, as a eminent member of the Worshipful Company of Dyers (he was Lord Mayor of London in 1626, elected Alderman of the City in September 1616, was Sheriff of London for the year 1616 to 1617 and was knighted on 20th May 1627) represents the Dyers’ rising fortunes and influence over time.

* After a portrait in Dyers’ Hall by the Dutch artist Daniel Mytens (1590 -1647)

16 – A member wearing an 18th century coat featuring the dyed woven and embroidered silk pattern designed by Anna Maria Garthwaite (in 1747) who was a globally recognised foremost designer of London Spitalfields Silks in the 18th century. Her pioneering naturalistic botanical designs which broke away from the previously stylised geometric patterns, influenced fashion for decades. As such the inclusion of this jacket within the artwork redresses the largely un-sung but significant contribution of female figures, and signifies the importance of design (involving the considered choice and balance of dye colours) to the Spitalfields Silks industry.

16a, 16b and 16c – The Maltese cross, fleur-de-lys and dove emblem of the French Calvinist Protestant Huguenots – representing the close-knit industry of Spitalfields’ French refugee silk weavers which Anna Maria became a part of. The story of Huguenot persecution in France (which led them to flee to England and establish their craft their in the 17th century) is represented by the figure of the Sun King, Louis XIV (16b) who in 1685 revoked the royal proclamation of religious freedom known as the Edict of Nantes (16c) previously granted by his grandfather and declared Protestantism illegal with the Edict of Fontainebleau – forcing Protestants to convert or find refuge in other countries.

17 – A member dressed in Baroque period attire as Sir James Houblon* (1629-c1700) who was a merchant of French Huguenot refugee descent and a prominent member of the Dyers guild which he first joined in 1654. A close friend of Samuel Pepys, he was elected Alderman for the city of London in 1692; was knighted that same year by William III; and became a Director of the Bank of England in 1694. He invested heavily in the English East India Company and Levant trades and was a Chairman of the Spanish Company of Merchants. He is shown holding a 50 pound note** featuring his brother Sir John Houblon (1632 -1712) who was also a prominent member of the Dyers; was Lord Mayor of London; became the first Governor (in 1694) of the Bank of England which he co-founded with James; was a Director of the New East India Company from 1700-1701 and Chairman of the Company of Merchants trading to Portugal.

* This figure is based on an historical portrait of James Houblon in Roman attire, attributed to the Dutch artist, Willem Wissing.

* * Withdrawn in 2014 but issued in 1994 on the 300th anniversary of John Houblon’s death in 1711.

18, 18a and 18b – A member representing the Crutchley family – prominent master dyers of the 18th century whose founder John Crutchley became a full member of the Worshipful Company of Dyers in 1710. He is shown in the uniform of a Navel Commander of the East India Company* denoting a commerce in dye built on maritime trade and the family’s connection to the Company as key suppliers. In one hand he holds a book from the Crutchley Archive (18a) – a rare collection of material (including dyeing instructions, pattern books, cash and calculation books) once owned by and relating to the family’s wool fabric dyeing business in Southwark, London. The recognition of this Archive by the UNESCO Memory of the World programme, as being significant documentary heritage for UK textile history, is represented by the medal (18b) in the figure’s right hand.

* The uniform is inspired by the one (of a later period to the Clutchley’s) currently in the Royal Museums Greenwich collections, dated c1830

19, 19a and 19b – An heraldic banner depicting a 17th century view of Southern India’s Coromandel Coast in South India – an ancient centre of manufacture and export for hand-dyed and painted Indian calico textiles whose huge popularity in the west during the 16th – 18th centuries due to their superior quality (characterised by brilliant hues, fast colours and pretty chintz patterns) posed a threat to English textiles. In front of this view is a portrait of Father Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux (19a), the 18th century French Jesuit missionary in South India who betrayed the trust of his Indian converts from the dyeing community by passing the highly guarded secrets of their craft on to his countrymen. Through this early act of industrial espionage France was the first to acquire the skills and knowledge of Indian calico dyeing and printing, and from there, it spread to Britain and other parts of Europe. Illustrations* showing the Indian method of printing chintz using chay root** (Indian madder) are shown emanating from the pages of Coerdoux’s bible. Below Coerdoux is the figure (19b) of Armenian craftsman, Jean Athen (1709-1774) who introduced the cultivation of madder into France .

*From a group of eight process samples (created c1919) in the Victoria and Albert Museum collections showing methods used in the 17th and 18th century.

** A natural red dye from the Coromandel Coast.

20 and 20a – A member in Georgian costume holding a Georgian era wine glass from the Worshipful Company of Dyers’ collection. On the table in front of him is a Royal Act of 1726 (20a) issued by King George I, permitting temporary free importation of Cochineal from “any port or place [whatsover]”, during a period of “interruption of the commerce with Spain” when British ships were not permitted to enter Spainish ports. This detail highlights how the dyeing industry and trade was influenced by politics and regulated by law.

21 – A member dressed as William Morris* – representing how the history of dyeing connected to the Arts and Craft Movement of which Morris was a founding member. Through this Movement Morris was especially known for championing hand-crafted, organic dye practices in rebellion against the introduction at that time of cheaper, aniline chemical alternatives. This rebellion was part of his wider efforts to challenge the mechanisation of commercial manufacture which he regarded as detrimental to the textile and craft industries. Morris’ interest in India’s ancient, natural dyeing techniques led him to perfect the art of dyeing with Indigo. In this respect, this figure within the artwork also represents the foreign contribution to Britain’s history of dyeing. The pattern on the figure’s jacket (Morris’ Brer Rabbit design) was specifically intended for the indigo discharge method which Morris perfected. His floral, paisley and elephant motif scarf is inspired by samples of 19th century turkey red dyed cotton textiles in the Turkey Red Collection of National Museums Scotland which were produced by Scottish manufacturers for the Indian market. The use of animal motifs in similarly patterned turkey red textiles made for British markets is said to have been influenced by the Arts and Craft movement in the later 19th century through designers like William Morris.

* Inspired by a black and white photograph of Morris, which The Singh Twins have adapted.

21a to 21d summary – As a researcher and innovator of dye techniques inspired by knowledge from India, William Morris is depicted alongside a group of objects denoting how research and knowledge sharing through intercultural exchange have similarly been and continue to remain an important part of the Worshipful Company of Dyers’ work. At the same time, these object highlight the Company’s spirit of collaboration. They include details 21a to 21d as follows:

21a – A page (adapted by the artists) from the June 1944 edition of the Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists. Both the journal and the society were founded in Bradford by the Worshipful Company of Dyers in 1884. The society now “works globally, with worldwide membership and is a centre for networking and community engagement amongst the coloration industry”.* The page reproduced in the artwork reveals the heraldic use of colour and has a footnote advertising ICI – the British company founded in 1926 which became a leading developer and commercial manufacturer of chemical dyestuffs (1926-1999), with close links to the domestic textile industry.

* Cited from the Society of Dyers and Colourits’ website.

21b – The Worshipful Company of Dyers’ / Society of Dyers and ColouristS’ research medal (front) which was instituted in 1908 (in concurrence with the Society of Dyers and Colourists), to be awarded annually for papers published in the Society’s Journal – “embodying the results of scientific research or technical investigation connected with tinctorial arts”*.

* Cited from The Worshipful Company of Dyer’s website.

21c – The Worship Company of Dyers’ / Society of Dyers and Colourists’ Research Medal (reverse side).

21d – Image advertising the Dye Chem World Exhibition and Summit held in India in 2021, representing a networking, educational and training event supported by the Society of Dyers and Colourists in collaboration with other dye industry organisations.

22 and 22a – A member in Victorian costume next to a Cathedral bell (22a) representing the Worshipful Company of Dyers’ charitable contribution towards the purchase of a Great Bell for St Paul’s Cathedral in 1881.

23 and 24 – Members dressed in the uniforms of 4th Battalion The Parachute Regimen and 617 Squadron ‘Dam Busters’, with whom the Dyers became affiliated in 1957 and 1989 respectively.

23a – an invitation card for the feast of Dashaine which is attended annually by the Dyers’ Prime and Renter Wardens and hosted by the Queen’s Gurkha Signals (whose badge is featured on the card). This symbolises the Dyers’ affiliation with this regiment (since 2015).

24a – The uniform belt of the 30th Signal Regiment which the Dyers’ adopted in 1960.

25 and 25a – A member dressed in a shirt representing the classic 1950’s to 70’s era of floral and paisley patterned, synthetic material featuring psychedelic colours that not only reflect innovations in man-made textiles and chemical dye development but also, how eastern aesthetics (characterised by bright, contrasting colour and bold arabesque motifs) influenced textile production, design and fashion during that period. This figure holds the menu (25a) for a swan dinner actually hosted by the Dyers at Clothworkers’ Hall in 1964.

25b – A classic 1960/70‘s prawn cocktail starter – which is one of the dishes listed on the menu held by a nearby figure.

26 – A member with a ‘Hi Vis’ vest and jacket (characteristically luminous yellow and orange with reflective silver/grey bands) that became part of the UK’s working landscape from the 1960‘s onwards but has it’s origins in the 1930‘s and an industrial accident at an American Heinz Ketchup factory. This figure represents innovations in the production of new synthetic fibres and florescent dyes with a practical function (e.g. safety, light reflective and water resistant).

27, 27a, 27b, and 27c – A member dressed as a surgeon – representing the association of certain dye colours and fabrics with particular professions. He is holding a computer screen (27a) with images exemplifying the medical application of dyes (e.g. as biological stains, for clinical diagnosis and as drug colourants) and the use of aniline dyes (in this case Methylene Blue) as disinfectant and fish medication for aquariums (27b and 27c).

27d – Image representing the negative health risk and sometimes lethal effects of certain dyes – in this case Scheele’s green (invented in 1775 by Carl Wilhelm Scheele) – a brilliantly vibrant and durable inorganic green dye which became extremely fashionable during the late 18th and 19th century but which was highly toxic because it contained arsenic. The image is based on an engraving and accompanying article featured by Punch in 1862 which highlighted the effect of arsenical dyes and pigments in clothing and accessories.

28 – A member wearing his traditional Barge Master’s uniform and badge.

29 – The Worshipful Company of Dyers’ Prime Warden, dressed as John Talbot – as he appears in another page from the Talbot Shrewsbury Book (see green 9), shown presenting the Book to Henry VI’s wife, Margaret of Anjou. This historical costume has been adapted slightly by the artists who have added the Prime Warden’s badge to the back of the robe.

30 – A member wearing his Worshipful Company of Dyers’ Renter Warden uniform and badge.

31 – A member dressed as one of the courtiers depicted in the Talbot Shrewsbury Book

32 – A member dressed as one of the courtiers depicted in the Talbot Shrewsbury Book

33 – A member dressed in his Worshipful Company of Dyers’ Clerk uniform and badge.

34 – The Worshipful Company of Dyers’ first female Liveryman.

35 – Henry VI shown symbolically presenting the 1st Royal Charter to the Worshipful Company of Dyers’ Prime Warden – re-enacting and therefore marking the 550th anniversary of his awarding of the original .Charter to the guild of dyers in 1471. Amongst other things The Charter gave the Dyers authority to control the quality of its craft and thereby the reputation of London Dyers. It also permitted the Dyers to legally own land and acquire their first Hall. With this grant, the Dyers became an incorporated body in the city of London.

35a – The Singh Twins’ digitally re-created version* of the medieval illuminated painting (from the Talbot Shrewsbury Book) which inspired the initial concept and starting point for the Dyers’ 550 commissioned artwork.

* The Twins’ version was re-created from a black and white line drawing of the illuminated painting which featured in a first edition (1843) of Henry Shaw’s Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages.

KEY – FOR DETAILS WITHIN THE ARTWORK NUMBERED IN GREEN:

1, 1a, 1b and 1c – A figure based on Walter Raleigh, in general representing an early age of colonial exploration and trade. In more detail, the figure’s eclectic clothing, the moth flying above him and the animals and plants upon which he stands, represent a range of natural raw materials (silk, wool, flax, leather, fur, feathers, muslin/linen, cotton and sleeves) and finished dyed textiles associated with the dyer’s craft. Some of the items of clothing such as the Kashmri shawl, chintz patterned calico jacket and ostrich plumes, symbolise the influence of western ‘discovery’ and colonisation on Britain’s history of fashion and textile manufacture. The figure is shown directing a spy glass towards the East (the right side of the artwork). It is focused on a turkey (green 3a) representing the Turkey red dye* which was coveted by the west. These details, together with the figure’s sword and a set of images beneath the lamb under his feet – depicting an African woman picking Arcacia gum (a mordant) from Senegal (green 1a)**; Africans gathering cochineal for red dye in South America (green 1b)***; and Indians labouring on an English indigo (blue dye) plantation (green 1c)**** – expose the darker side of colonial history connected to the story of dyeing. One involving commercial espionage, enslavement and the exploitation of the resources of conquered and colonised people around the globe. The theme of colonial conquest and exploitation is further represented by the figure’s fur lined, pearl encrusted cloak (representing colonial wealth) which is inspired by the one worn by Sir Walter Raleigh***** – the English explorer and military and navel commander who was granted a Royal Charter by Elizabeth I to colonise and commercially exploit any lands in the Americas not already claimed by a Christian monarch. Raleigh was also a privateer who procured tons of indigo and cochineal for England (“enough… to be use in [the] realm for many years”) by capturing and plundering the cargo of Iberian ships. As such, his sword also represents how conflict and piracy between western nations vying for control of lucrative dye substance markets was also part of dye history.

* A brilliant scarlet colour introduced into Europe through the Turkey red printed fabrics exported from India and first perfected in the west by the dyers of Holland and France who were “determined to keep the technique secret and despite espionage expeditions and financial incentives from the Society of Arts in London, it was not adopted successfully in Britain until the 1780s, first in Manchester and then Glasgow”. (cited from National Museums Scotland website article, The Turkey Red process.)

** From a 1900’s trade card

*** From a woodcut print, dated 1835

**** From a Copperplate engraving, dated 1778

***** As depicted in a 1588 portrait by an unknown English artist, now in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery.

2 – A portrait* of the Yorkist monarch, Edward IV who in 1472 confirmed the first Charter awarded by the Lancastrian monarch Henry VI to the Dyers in 1471. The series of civil wars known as the Wars of the Roses which eventually led to Edward claiming the throne from Henry, are referenced in the bottom left corner of the portrait. The artists have depicted Edward holding a publication (Bartholomaeus Anglicus’ ‘De Proprietatibus Rerum’ of 1482) which he is known to have owned a French translation of (titled, Le Livre de la propriété des choses) containing one of the earliest medieval paintings of dyers at work (see red 10c). The dyers are shown soaking red cloth in a heated barrel.

* The Singh Twins’ adapted and colourised version of an antique black and white engraved copy (dated c1740) of a 16th century painting of King Edward IV.

3, 3a, 3c and 3b – A portrait of Elizabeth I who granted the Dyers a Ratification of Ordinances in 1578 enabling them to control the craft of dyeing. In this image (which is the artists’ adapted, colourised version of an 18th century black and white engraved copy of a painting of Elizabeth, known as the ‘Rainbow Portrait’) the artists have added the coat of arms of the Levant Company (green 3c). The company was formed by a merger of the English Venice and Turkey Companies under Royal Charter of Elizabeth I in c1592. The charter granted a monopoly to trade directly with Turkey which controlled the major trading routes for Indian indigo which was highly prized in the west. On the gilded frame of Elizabeth’s portrait, a figure of satan (green 3b) is shown eating indigo dye plants. This represents how (in response to the threat that the craze for this superior, deeper, more colour-fast) source of blue dye was posing to England’s ancient home grown blue woad industry during Elizabeth’s reign) Indian indigo was vilified as the ‘devil’s food’.

4 – King James I of England who in 1606 reaffirmed the Charter granted to the Dyers by Edward IV. In his portrait (which is a colourised, adaptation of a 19th century antique steel engraving) the artists have added the Royal Coat of Arms and a sapling mulberry tree representing the monarch’s attempts to establish an English silk industry.

5 – Queen Anne Stuart who awarded an updated (and current) Royal Charter to the Dyers in 1704 granting jurisdiction to the Company over “the trade in London and within 10 miles thereof, with the power to enter and to search in every house, shop and warehouse ….. and to take for such search once every quarter, 1 shilling towards the expense”. The artists have incorporated details of the original Queen Anne Charter (which is still in the possession of and governs the Dyers till this day), into the background of her portrait. Bottom right of Anne’s portrait they have added an image of her royal seal. On top of both Queen Anne’s and King James’ gilded frame , are garlands of wild and cultivated flowers and fruits used for home dyeing. They include croci; peonies, blackberries and pomegranates.

6, 6a, 6b, 6c, 6d, 6e, 6f, 6g, 6h and 6i – This group of imagery relates to the story of Mauveine purple (also known as aniline purple and Perkin’s mauve) as one of the first synthetic chemical aniline dyes to be produced. It was invented by the British chemist William Henry Perkin (6a) in 1856 and made purple (formerly the preserve of nobility) affordable to everyone. The mosquito (6b) points to Perkin’s accidental discovery of the dye whilst attempting to development a treatment for malaria. A young Queen Victoria (6) stands on the blue heritage plaque (6c) marking the site where Perkin established the first synthetic dye factory in the world. She is depicted in the mauve coloured dress which she wore for The Princess Royals’ wedding in 1858. Her wearing of this is said to have influenced the popularity of mauveine purple within Victorian high fashion – a frenzy which was satirically referred to at the time as ‘mauveine measles’ by ‘Punch’ magazine. Next to her are cross-section diagrams of fabric dyeing machinery (6d and 6e) denoting how Perkin’s discovery and his factory method of producing mauveine revolutionised the craft of dyeing – influencing the emergence of a commercial chemical dye industry which led to the further development and mass production of a whole range of different synthetic aniline dyes in myriads of new brilliant hues that changed the colour palette of textile design and fashion forever. One of the machines (6d) is said to be an ‘eco-friendly’, water preserving air-flow dyer intended to “promote localised production in regions of the globe that lack the water required for traditional methods”. As such, it simultaneously represents how large-scale global commercialisation of dyeing has impacted negatively on the environment but also how the industry has made attempts to redress this problem. Emanating from the machinery is a pattern composed of chemical formulae (6f) associated with synthetic dye manufacture. A lilac coloured Victorian six pence postage stamp (6g) represents the application of Perkins’ mauve beyond the world of fashion. Whilst two late19th/early 20th century textile trade labels (6h and 6i) pertaining to chemical dyes both manufactured within and exported to India by western companies (some in collaboration with Indian companies), highlight the global impact which Perkin’s discovery would come to have on countries once coveted for their hand-crafted natural, organic dyes and dyed fabrics.

7 – Ballet dancer, artist’s paint palette and theatre masks representing the Dyers’ long-standing charitable activity in support of the Arts in the UK.

8 – An image highlighting the importance of the dyer’s craft as part of the heraldry and pageantry of nobility in England as exemplified by the material culture (tents, uniforms, flags) of warfare depicted in the image.

9 – An 1843 depiction the court of Henry VI (copied from the medieval Talbot Shrewsbury Book). This image inspired the costume worn by the Prime Warden (red 29)

10 and 11 – portraits of Henry VI and his Queen (Margaret of Anjou) kneeling in prayer at court. They represent royalty as patrons of the dyers’ craft and how the craft contributed to the splendour and spectacle of court life (as exemplified by the decorative textile wall hangings, table cloth and costumes seen within the portraits). The two portraits are copied from a 16th century tapestry known as the Coventry Guildhall Tapestry. As such they specifically also highlight the association of dyeing with that art-form and how the early craft of dyeing is preserved through historical objects that are part of Britain’s collective material heritage.

12 – Monarchs and nobility dressed on all their finery kneeling in the chapel of St George. This imagery represents the church and royalty/nobility – traditional patrons of the dyer’s craft.

13, 14, 15 and 16 – The crests of four London based educational institutions supported by the Dyers. Namely, Boutcher School, Archbishop Tenison’s School, St Saviour’s School and Norwich School.

17 – The Worshipful Company of Dyers’ coat of arms (confirmed in 1577) as it appears today incorporated as a stained glass panel within the main window (featured in the artwork) of the Court Room at Dyers’ Hall. The emblazonment (as published on the Worshipful Company of Dyer’s website) is:

Arms – Sable, a chevron engrailed Argent, between three bags of madder of the last, corded Or.

Crest – On a wreath of the colours, three sprigs of a graintree erect Vert, fructed Gules

Supporters – Two panthers incensed rampant guardant Argent, spotted various colours, fire issuing form their ears and mouth proper, both ducally crowned Or.

Motto – Da Gloriam Deo (Give Glory to God)

The decoration of the main window between the two central pillars also incorporates stained glass representations of both indigenous British and foreign imported flowers and plants (added by the artists) associated with the craft of dyeing. The four main window panes immediately left and right of the coat of arms depict Kermes Oak, Logwood, Safflower and Old Fustic. The Kermes and Safflower panes are surrounded by Chamomile flowers. The three panes above this are surrounded by marigolds and the top most register of the main middle window contains madder plants.

KEY – FOR DETAILS IN THE ARTWORK NUMBERED IN BLUE:

1 – The Great Fire of London in 1666 which destroyed the first two Dyers’ Halls and most of their historical records.

2 – Three stars representing the tenement called ‘Three Starreswas’ (Lez Thre Sterris) granted to the Dyers on 14th September 1484 which became the site of the first two Dyers’ Halls, seven of its original almshouses (est. 1545) and several dye houses, workshops.

3 – A blue Heritage plaque in London which today marks the site of Three Stars where the Dyers’ were based until 1681 when the Dyers relocated their premises after their second Hall on the site which was re-built after the Great fire), burnt down in another fire.

4 – A phoenix (representing rebirth and reinvention) flying upwards to a framed 18th century depiction of the Dyers’ third Hall (completed 1770) on Dowgate Hill where the Dyers relocated after 1681 and built their forth and current Hall in 1840 after the previous one kept collapsing and eventually had to be demolished.

5 – An image of a dyehouse leased from the Mercers – viewed from the South Bank of the River Thames and showing fabric hanging from the windows – as depicted (and inspired by) an engraving of 1647 by Wenceslaus Hollar.

6 – A visual representation of a rhyming verse used to recall the originally five (now 7) Livery Companies of London which are governed by Prime Wardens rather than a Master – of which the Dyers are one. Namely:

“A fish with golden scales is dyeing within a blacksmith’s basket lying”. – (denoting Fishmongers, Goldsmiths, Blacksmiths, Basket Makers and Dyers)

7 . London Bridge – a landmark for locating Dyers Wharf.

8 – Detail from a rare tapestry* dated 1654 containing perhaps one of the earliest known representations of the Dyers’ coat of arms. This imagery highlights a skill (that of yarn dyeing) which was an important part of the dyers’ craft.

* In the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

9 – A Tudor ship carrying Indigo plants and spices and with Indian textiles for sails – one of which is also emblazened with the English East India Company (E.I.C) coat of arms. These details represent the dyers’ imports of Indian Indigo and how trade in dyes was part of a wider global commerce in luxury goods from India and further East during an age of exploration and colonial expansion under a company (E.I.C.) which was granted a monopoly in such trade by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600. The name ‘Roe’ on one of the ship banners is a reference to Thomas Roe (c1581-1644) whom King James I, at the bequest of the E.I.C., sent as a royal envoy to the Mughal Court at Agra to secure trade in India.

10 and 10a – Spotted leopards from the Dyer’s coat of arms.

11 and 11a – Medieval minstrels (11a) playing along to the Dyers’ Swan song (11).

12 – The Dyers’ ceremonial barge, purchased in 1453 on instruction of London’s Lord Mayor for use in the Mayor’s Procession. This represents the Dyers’ growing prominence (making them eligible to take part in the pomp and ceremony of the city) and traditions of pageantry but also at times, their declining fortunes (symbolised by the barge having only 9 instead of 12 oars) as they were later forced to sell this status symbol during a time of financial hardship.

13 – The Dyers’ new Heraldic Badge, commissioned for the Dyers’ 550th anniversary in 2021. Its design includes a bag of madder from the Dyers’ coat of arms and a swan representing the Dyers’ right (together with the Vintners) to take part in Swan upping – involving the rounding up, counting, assessing and marking of swans and cygnets. In accordance with how in earlier times the Dyers’ once marked any swans they caught, the bill of the swan in the new Heraldic Badge is shown with one nick in it. The swan’s coloured spots allude to the work of dyeing.

* cited from Royal.uk website

14 – A submarine (HMS Vanguard) representing the Dyer’s affiliation with the Royal Navy, first established in 1987.

15 – Image of ‘a swan with two necks’ representing a common pub name and sign in UK today dating back to the 16th century which demonstrates how the tradition of Swan upping has impacted on popular culture through the ages. The phrase is said to be a pun on ‘a swan with two nicks’: a reference to the Vintners’ practice of marking the bills of any swans they round up during Swan upping with two nicks. The Royal swans remained un-marked.

16, 16a and 16b – Two Worshipful Company of Dyers Barge Masters (from different time periods) engaged in Swan upping (see blue Key number 13) – a practice of counting, assessing and demonstrating the right to own swans on the Thames which dates back to the 12th century when the British Crown claimed ownership of all mute swans which were considered important food for banquets and feasts. As the date behind one of the figures denotes, the right to own swans (The Royalty of Swans) and take part in Swan upping was granted to the Dyers in 1550*. The figure on the left (16a) is wearing the modern day Dyers’ Barge Master’s blue blazer (distinguishing them from the Vintners who wear red). The figure on the right (16b) wears the tradition blue Dyers’ Barge Master uniform. Today, Swan upping is more about conservation of swans on the Thames and the bills of the birds are no longer nicked.

* Cited from the interactive timeline on the Worshipful Company of Dyer’s website.

17 and 18 – The Dyers Almshouses in Islington which were built in 1850 and The Dyers Almshouses in Northgate, Crawley which were built between 1939 and 1971. The Dyers first founded Almshouses in the City of London in 1545 to care for dyers and /or their families who were elderly or had fallen on hard time.

* Inspired by an engraving of 1884.

19 – Woad and Weld plants – two natural sources of dye.