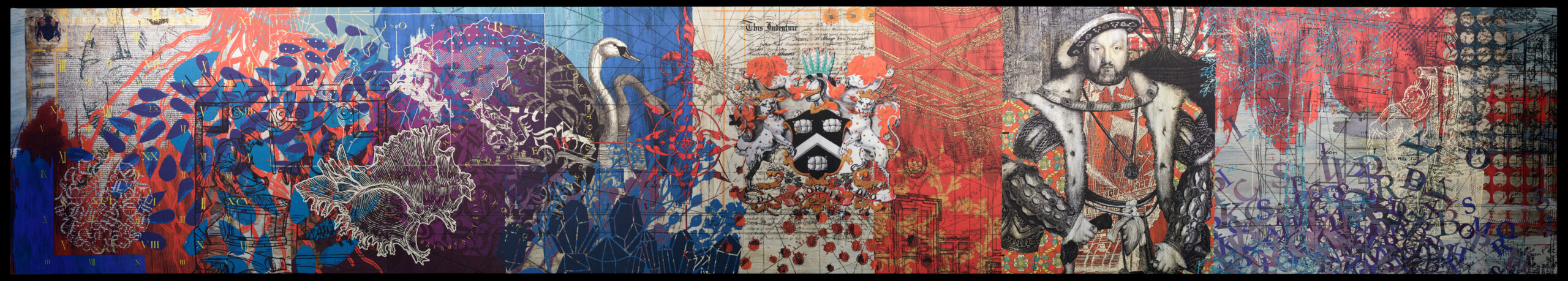

This frieze is designed to represent the history and development of natural dyes. The complex

layered style is intended to evoke a sense of the passing of time, evolution and change. A colour

palette of red madder, indigo blue, cochineal, Tyrian purple, woad blue and a variety of earth tones

derived from logwood and kermes reflect the variety, vibrancy and richness of coloured dyes derived

from the natural world.

Inspired by Richard Haklut’s Principle of Navigations, London 1599, and referencing the East India Company’s promotion of Elizabethan overseas expansion, a backdrop of an antique world map suggests the global connections and discoveries involved in the dying industry.

The chronology of natural dyes commences from left to right with rich painterly washes of natural

dye colours, which provide a backdrop for a tangled web of madder roots. A delicate sketch of

Tutankhamen’s mask references the discovery of madder root in the Royal tomb, whilst the early

adoption of text is represented by a pattern of gold Roman numerals which overlay an example of

the early Worshipful Company of Dyers’ Charter document.

By contrast hand cut collages of English Blackletter represent the communication of trade and

development of dye recipes. An early illustration showing the vat dying process in action sits in the

midst of a flurry of Indigo leaves in the stunning shades of blue yielded by the alchemy of the natural

indigo dying process. A world map illustrates the location of species Rubia and of Turkey red dying

and a drawing of a tyrian shell sits in a collage of purples and crimson, contrasting with blue tones of

fragmented blocks of alum crystal, used as a mordent in the dying of cloth.

The magnificent Dyers’ Coat of Arms takes centre stage with two swans peeping out to the left, and

below scurry an army of kermes beetles which are used in the production of red dyes. To the right

of the frieze a resplendent Henry VIIIth wears a richly coloured and bejewelled doublet, in shades of

red and gold, which illustrates one of the Royal shipping vessels and represents the status and value

cloth during the powerful Tudor dynasty.

Archive architectural plans of Dyers’ Hall Dowgate Hill, London, provide a backdrop to the right-hand

side of the frieze, overlayed with a splash of cochineal red, a drawing of a brazil wood tree and a

boiling caldron from which spill a jumble of printed letters, in shades of logwood mauve. A classic

textile polka dot motive, in the shape of the wax Dyers’ Hall seal, is detailed with several of the Dyers’

Hall Freedom bearers of the 19th Century.